While vacationing in Prince Edward Island, I noticed bilingual—sometimes trilingual—labeling everywhere. French, English, and Mi’kmaq appeared on roadside signs and in the national parks. French and English on every box and bag in the grocery store. That got me thinking about learning French.

I studied two years of French in high school and two years of German in college. Back then, language study felt useful mostly for showing me the roots of English grammar and vocabulary. French and German helped me understand my own language.

In my forties, while working as a librarian in a town with many Spanish speakers, I signed up for a few lessons in Spanish to help me understand basic phrases. Struggling to speak another language gave me empathy for English language learners.

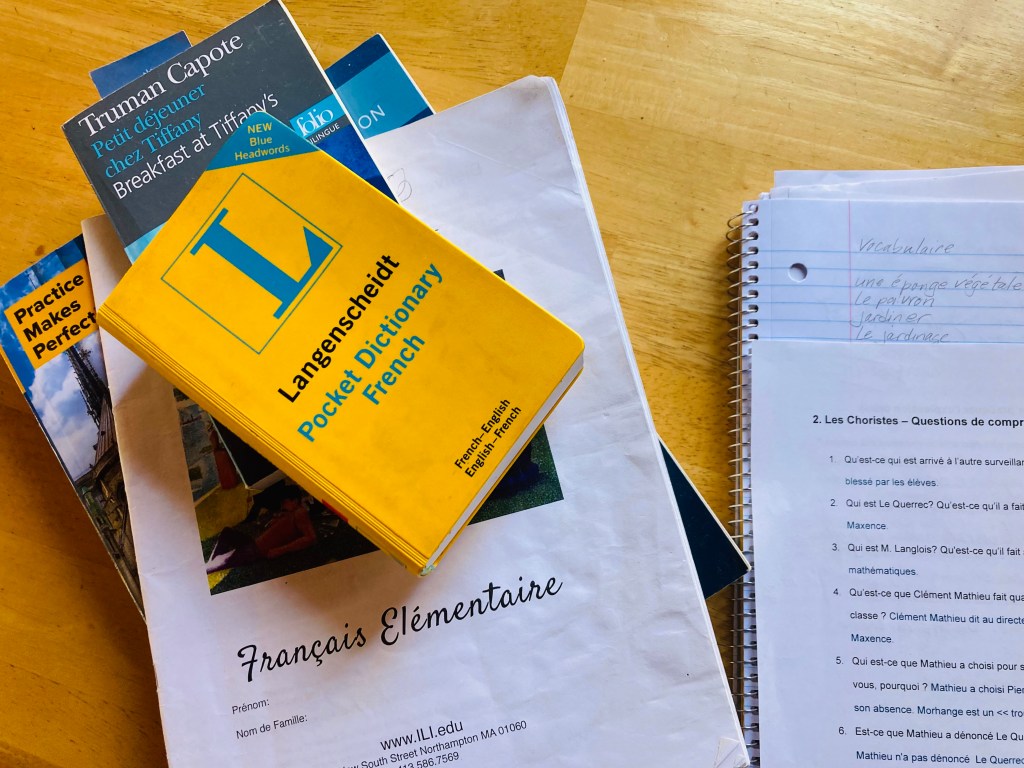

Now, in my sixties, I hadn’t really considered returning to language study—until I saw that bilingual package of Robin Hood flour on the shelf in Sobeys. The idea of studying French intrigued me. I knew that the International Language Institute in Northampton, Massachusetts, had a stellar reputation. I pulled up their website on my phone and registered for a class.

Learning a new language is a workout for the brain. New vocabulary draws on semantic memory (the meaning of words) and episodic memory (the context in which words are used). Research on the cognitive benefits, specific to foreign language learning for older adults, is inconclusive thus far.

What is beneficial? Getting out of the house, being social, and learning something new.

“The brain operates via principles of neuroplasticity. In other words, your brain is responsive to use—that’s when connections form. Connections strengthen your cognitive health, and it’s to your advantage to continuously build up those sets of connections, whether it’s through hobbies and skills, maintaining complex tasks, learning new information, learning new languages, or whatever is of interest to the individual. In the long run, this practice will be very beneficial compared to individuals who are intellectually sedentary.”

— Roy H. Hamilton, MD, MS, McKnight Brain Research Foundation

Ah, but forming a new habit…

I began French lessons last year. For the first three months, I fumbled. Most of my classmates were 60+ years old. Josh, our instructor, clearly understood the challenges we faced—searching for words, unfamiliar pronunciations. He kept us engaged with fun, active learning techniques.

After a few months, I realized that I wouldn’t improve unless I studied between classes.

I am still inconsistent with this. To some degree, I’ve had success with a technique called habit stacking—linking a new practice with an established routine. For example, I always (always, always) have a mug of tea in the morning. My tea needs to steep. While it steeps, I usually do a bit of yoga or a set of crunches. I talk myself out of it sometimes, but I do it often enough that yoga during steeping has become a secondary habit.

I’ve tried to apply this idea to language study, though I haven’t found the perfect pairing yet. With one exception: when I do my crunches, I count in French.

I’ll keep experimenting—and I’ll update you on my progress as I build stronger French study habits.